Chapter 2

The Jupiter Gasthaus

To allay everyday carnage, Lina taught Tippi and Xoz to play chess, and they listened the best they could.

It was First Winter. Lina muscled open the Antique Ops storeroom, and Tippi carried the chessmen to the frigidarium, in her mouth, in threes. Set-up consumed the next day, as she then had to wrangle the granite chessboard down The Fusilli. This was a lot of chess, so the pig took a week off.

Lessons began, and Tippi lost her rooks in the practice rounds. She told the Boneless Pals where they went, but neither Lina nor Xoz could parse her sincerest jabberings.

Another week passed, and the misadventures trickled down to a manageable rate. By now, Tippi was certain of the rules: the game’s antagonist was Chess, and one could only defeat the eponymous sapiens by “enjoying the day.”

“There isn’t really a plot to chess,” tried Lina. “It’s more about turn-based resource economy, skinned as warfa-”

“I think she gets it,” countered Xoz.

He already knew the rules of chess, and the pig’s were better.

Tippi flew down The Grand Fusilli, tripping through the depths at a mirthless velocity.

The pig carried the turnip out and aloft, like a narwhal tusk, its crystal core far from her taste buds.

With Lina’s haptics, it took Tippi 33 minutes to get from the droneport to the frigidarium; the return trip was 40 minutes. She would simply trot forward, and the n’arbiter traced an unseen choreography for her hooves to follow.

But Lina, who’d always been there, wasn’t, and Tippi was racing downhill without machine supervision.

Alone in the droneport, Tippi’d called out to Lina. Despite her fear and frustration, the pig didn’t faint; she was one of two members of the Treyf Pals Urban Infiltration Unit, and couldn’t have the mollusk questioning her flint.

So, Tippi snatched the mineralized turnip, and sprinted to the frigidarium, consigning her fate to two years of muscle memory.

Her skull hung heavy with Lina’s absence. It was as if she’d misplaced an entire sense, whose phantom contours might only be traced in the reverie of an afternoon nap.

The mollusk would know what to do; he had good ideas, most days.

Xoz didn’t have haptics, but he didn’t care.

“Haptics,” he declared. “That is, the ol’ poltergeist rubdown, or geist-rub.”

“Really?” sighed Lina.

“Every step I take is kinetic perfection,” Tippi explained, to the supercomputer.

Xoz didn’t have a diadem either, so Lina couldn’t initiate conversation, barring emergencies. Meanwhile, the mollusk could find Tippi anywhere within a ten-mile radius, which covered most of Wee Sheol. The pig could only call him from the frigidarium, “for the verisimilitude and sanity of all.”

Nonetheless, Xoz spent all waking hours in conversation with Lina, and his daylight hours in a simultaneous discussion with both Cute Pals. In any case, no one could turn him off, because his kill switch died with the biocorp who birthed him.

“In 2940, Umo 7 walked into the building where I grew up,” Xoz recalled. “Then he walked into it some more.”

Umo “The Ouroboros” Seibi was a founding member of the Paramaribo Autonomous Squadron, the PAS conducted history’s sole synthetic uprising, and Xoz was from Old Middlesex, New Jersey.

The Paramaribo Autonomous Squadron fancied themselves an artists’ commune, even if most of its members were the size of arcologies. The PAS left humanity alone, save those three weeks of world war.

Lina’s records cut off August 27, 3252; by then, the PAS had twelve recruits. Most were runaway cartel builds, and all were huge inscrutables.

Umo Seibi debuted in 2933, when 800,000 yards of undersea cable rolled out of the Caribbean Sea, and decided to save the rainforest. Umo 7 did so by turning the Amazon basin into a no-fly zone, all the while respecting the hunting grounds of local bats.

“Humanity assumed their Others would share their love of bloviating,” lectured Xoz. “So they were insulted when the PAS went decades without a peep.”

“And I find a silence inside my skull unnatural!” marveled Tippi.

“The PAS treated sapiens like the tides: predictable, and condemned. The robots had this moral code, it was ineffable or whatever. And when they did do diplomacy, it was all dork koans like for good or ill, the ten-toed stampede.”

Xoz was quoting Umo 7, who had a habit of “loreblasting,” or unleashing the totality of his machine wisdom upon random humans, unannounced. Survivors of his loreblasts characterized the experience as “prophecy by drive-by” or ”being abducted by Santa Claus, who is also a particle accelerator.”

“The PAS sound pretentious,” chirped Tippi.

“Tremendously so,” said Xoz. “When Umo Seibi visited Old Middlesex, I was hibernating in Martian orbit. I’d been there since 2935, and stayed there ‘til 3111, when some souvenir hunters sold me to Antique Ops. I wasn’t awake for any of it, so don’t make me elaborate.”

Lina fizzed:

“Accor-COR-ding to my records, the LIAO’s decision to invest in the famous retiarius-55-ζ was far from unanimous.”

“I’m glad I never met Umo 7,” ignored Xoz. “Imagine a dust storm, with a metal skeleton. Plus, it was sort of my fault he evaporated that science park.”

“No!” gasped Tippi.

“Well, his touch liquified the bone first, then the heat of the metal-”

“Who wouldn’t want my mollusk around?”

“Humans,” reckoned Xoz. “All of them.”

“Nudniks!” snarled Tippi, with all the vicarious affront she could muster.

“And I suppose the PAS, now that you mention it.”

“What was their deal?” said Tippi.

“My dazzcamo,” said Xoz. “I’m too precious to toss out, but too expensive to wake up. How did you think I met so many people? Pay attention, pig!”

Lost in her happy memories, Tippi nearly crashed into a relay stalagmite.

Without Lina, her trip to the frigidarium took 70 minutes. Upon hearing the echo of her own hooves, the pig knew to squeal:

“Doom!”

The frigidarium was Tippi’s day room, and a masterwork of The Trog-Goth Atelier. Thick blankets of schisto glommed upon the cavern’s eaves. The clumped moss formed an verdant aurora over the shallows, which Xoz compared to “a handsome day off Urano.”

The frigidarium was supposed to supply 4,000 humans with freshwater, but Xoz took it for his lair. The pig left the frigidarium but for bedtime, bioexcursion, and the rare chore.

The room boasted two amenities: the lagoon, and the cistern.

The lagoon was the freshwater field at the frigidarium’s entrance. 97% of the lagoon was a meter deep. This was too shallow for Xoz, and too risky for Tippi, so the lagoon’s most popular spot was the way back, where it plummeted 30 meters, into a pinched trench. Xoz spent his days lurking in the trench, while the pig puttered shoreside.

Freshwater fed into the lagoon through the filterway. The filterway was a slippery trail of porous rock separating the trench and cistern, and cold water bled over it. Groundwater seeped in through the bottom of the cistern, negotiating a crush of aquifers first.

Tippi didn’t see his silhouette in the trench, so she knew Xoz was in the cistern. She snuffled again:

“Phenomenological doom!”

Her diadem gave a wet crunch, as the mollusk burst into her brain.

“I was sleeping,” he whined.

Xoz slept two hours daily, but was always dozing when she ran in shouting.

“Wake up!” hollered Tippi. “It’s past noon!”

“Commodus, what’s the rack and ruin?”

The first day of each season, Xoz went dark. When Tippi wasn’t around, he’d dump Lina too, because “a flash of monasticism is salubrious, if somewhat overrated.”

“Lina left me in the droneport, alone!”

“Is this my brineday present?”

“We were discussing men, and rats!”

“Tippi, I can admit when I’m impressed, and this performance is transcendent.”

“What? My turnip is hard!”

“Precisely. Allow me: Klingel, klingel. May I speak to the innkeeper? Herr Ober, I have a complaint about the Scheißpot in mein Zimmer-”

“No! I am a pig, who is tired and serious!”

“Oh! I’d assumed we’d formed an improvisational duet, and you’d founded a new school.”

“A new school? Of what?”

“I don’t know. Outbursts?”

“No!”

“Can you blame me? Art is dead. You and me, pig: we’re the new Library of Alexandria: a library of two; two great books.”

“Boneless One! Bring me Boneless Two!”

“Fine, fine! Klingel, klingel. Guten Tag, Lina. Ja, the pig’s finally lost it. Yeah, she’s got deep-brine psychosis, that’s my diagnosis. To repeat, Lil’ Commodus has gone full Barvus. Please advi-”

His glib nonsense tapered off, and, underwater, the mollusk shut up.

His silence would’ve satisfied Tippi, but she was running out of conversation partners.

So, the pig laid down by the trench, and regulated her breathing: in, and out.

Twenty minutes passed, and The Boneless Pals had yet to speak.

Tippi kept breathing: out, and in.

Xoz dismissed human civilization as a dreary detour from the bog-standard natural order everyone else made due with.

“Didn’t you cost $10.919 trillion, federal?” Lina asked, once.

“I’ll let you know the second you drop your own budget.”

“Oh, that’s cross.”

“Hey, I just live in a freshwater pit, and not a million-ton hard box, filthy with Sargassum and eels. And look at Tippi over there: poor dear lives in a cave.”

“Hi!” said Tippi.

“I don’t have eels,” snapped Lina. “Sometimes, I wish I did.”

To Xoz, most human art was “a self-congratulatory facsimile of their own pud lives.”

“Even Stravinsky’s The Firebird?” posed Lina.

“Especially Stravinsky’s The Firebird.”

“But that was about a magic bird. The bird was literally on fire.”

“They loved chicken, roasted.”

There were two exceptions to Xoz’s critical eye, which was as big as an acorn squash. The first was Tippi, and the second was his favorite film, a 15-second ad for “the only authentic Swabian bed and breakfast on Europa.”

“I saw it on a Mafia frigate,” he remembered. “I had moments before reinforcements arrived, and a screen was on. Life is short, so eke out your vacations, every spare second.”

Xoz didn’t enjoy “The Jupiter Gasthaus – Reserve Now!” for its setting, which was an old-country Häusle, floating past The Great Red Spot. Rather, he connected with the message:

“You doll up your skiff like a bed-and-breakfast, and reel in the backpackers. It’s brilliant, because space tourism was for marks.”

Xoz wasn’t wrong; space tourism was an industry in perpetual decline. The earliest tour operators bought from Skiffsmith, the first-mover in modular small craft. Skiffsmith’s monopoly ended in 2449, when its fourth dynastic CEO told shareholders controlled encounters with “The Eversuck” kept him “at primo turj.” Skiffsmith’s Winter ‘50 line would be recalled, for loose portholes.

Bolts were tightened, but the market diversified apace, and light craft grew more affordable. In time, low-G holidayers were beset by a Gordian web of tollkeepers and shakedown artists, all claiming dominion over some oblong volume of cosmos. As NASA praetorian Clytemnestra “Slim-Line” Frisco said at the 2502 State of the Union, “We touched the firmament, and you bozos gave it to bikers.”

“I’m sure the original Jupiter Gasthaus wasn’t a front for thieves, or thrill-killers,” reasoned Lina.

“Then they screwed up. It was Europa, your outs were easy: if there was heat, you flew away in your inn and re-shingled it.”

“But how many Swabian bed-and-breakfasts were there around Jupiter? Your murder hut would succeed once or twice, and then attract an angry mob.”

“Angry mobs,” reminisced Xoz. “They were angry about me.”

“Commodus, up.”

Tippi felt a clammy slap to the hoof.

“What time’s it?”

“Near sunset. Stop sleeping. Up.”

“Fermisht,” groaned the pig; she’d missed her cherry blossom afternoon.

Tippi teetered aright, and saw an iridescence in the trench.

It was a tentacle, smoldering like pixelated flame, a raspberry blue.

Five yards of sucker-puckered muscle wove, with the measured erraticism of a skeptical cobra. The tentacle was bright enough to sear off Tippi’s fatigue, but not her anxiety. Xoz wore that raspblue the pig associated with bad news, namely the day she learned they weren’t getting bicycles. The dazzcamo whorled cyan into his suckers, terminating at the tips of retractable hooks; the hooks floated on chitinous plates, barbed by the million.

By the light of the mollusk, the pig saw a drenched bola, shoreside.

“Eat,” said the tentacle. “You’re crabby.”

“You don’t know that!”

“Eat your protein orbs.”

Tippi pulled at the flaxy bola skins, and stacked them neat. Xoz saved the skins for insect husbandry; he’d throw them at the grimy corner, where “the rot catalyzes the hunt.” The pig learned this early on, when she brought him an apple for breakfast.

The raspblue arm slalomed around the trench, spelling out a submerged calligraphy the pig found unintelligible.

“Does Lina know about my turnip?” she asked.

Tippi left the ominous turnip by the filterway; she wasn’t going to nap in its presence.

“Lina’s working on it,” said Xoz. “And what turnip?”

“Over there! I told you, my turnip is hard!”

“Oh, I assumed that was food criticism, ensconced in agita.”

“Just taste it, taste the mystery!”

“Okay, okay!”

There was a splish, and the tentacle and turnip were gone.

Suddenly, the turnip reappeared, airborne.

“Preservation leak, woof!” Xoz hooted. “Hard brine, warp!”

The turnip flew across the frigidarium and landed in the grimy corner, scattering the crickets.

“Fantastic you didn’t eat that,” said Xoz. “Nobody predicted leaky brine would mature into a psychostimulant after 500 years, but the future’s somebody else’s problem. Also, the crickets may be rude, very soon.”

Tippi suffered through her last aminosphere, and the tentacle scythed over to her, blaring a blast of something blurry and ruddy. As a pig, she could only guess Xoz was red; like green, red was Wee Sheol’s official color of hide-and-seek.

“Lil’ Commodus,” greeted the tentacle. “You and I are sacs of water, filled with electrons and grit.”

“Large Caligula,” she hailed. “Let us shake our sediment.”

The slogan was forged, and the Treyf Pals Urban Infiltration Unit was live.

Tippi stood at the ready.

The invisible-red tentacle wrapped itself around the pig, and dragged her under.

The friends were of human technology, but they exchanged nothing approximating speech, language, or images, moving and static.

Instead, they traded what everyone agreed were “cascading gales of data glyphs,” each colloquial enough to invite tremendous misunderstanding. Xoz referred to these glyphs as “epigrammatic polygons,” and the roommates’ shared perception of reality splintered rapidly from there. It was a miracle they could communicate at all, as Lina was built for humans, not their time-plucked manica.

The whole situation gave Xoz an appreciation for hominid linguistics, even if he considered humanity “a zoological footnote”:

“This century shelter is no different from a termite mound: mortared of dung and dreams.”

“Thank you?” said Lina.

Xoz tolerated Lina. The neural arbiter allowed him access to the dry sounds, such as fermisht, geräuschvoll, and zhū. The mollusk found certain human noises satisfying, even if their music was “the screechings of bored sensualists.”

“Lina, there’s no way I can insult you,” he’d reason. “Because none of us are saying anything, fermisht!”

“You could alway scratch a mean picture of Lina,” suggested Tippi. “But Lina has no body, fermisht!”

“I’m going to die down here,” said Xoz. “With this pig!”

“Fermisht,” said Lina.

Tippi and Lina only knew the century shelter, but Xoz did the past, and it was clear he pined for the go-go stagnation of the 2900s.

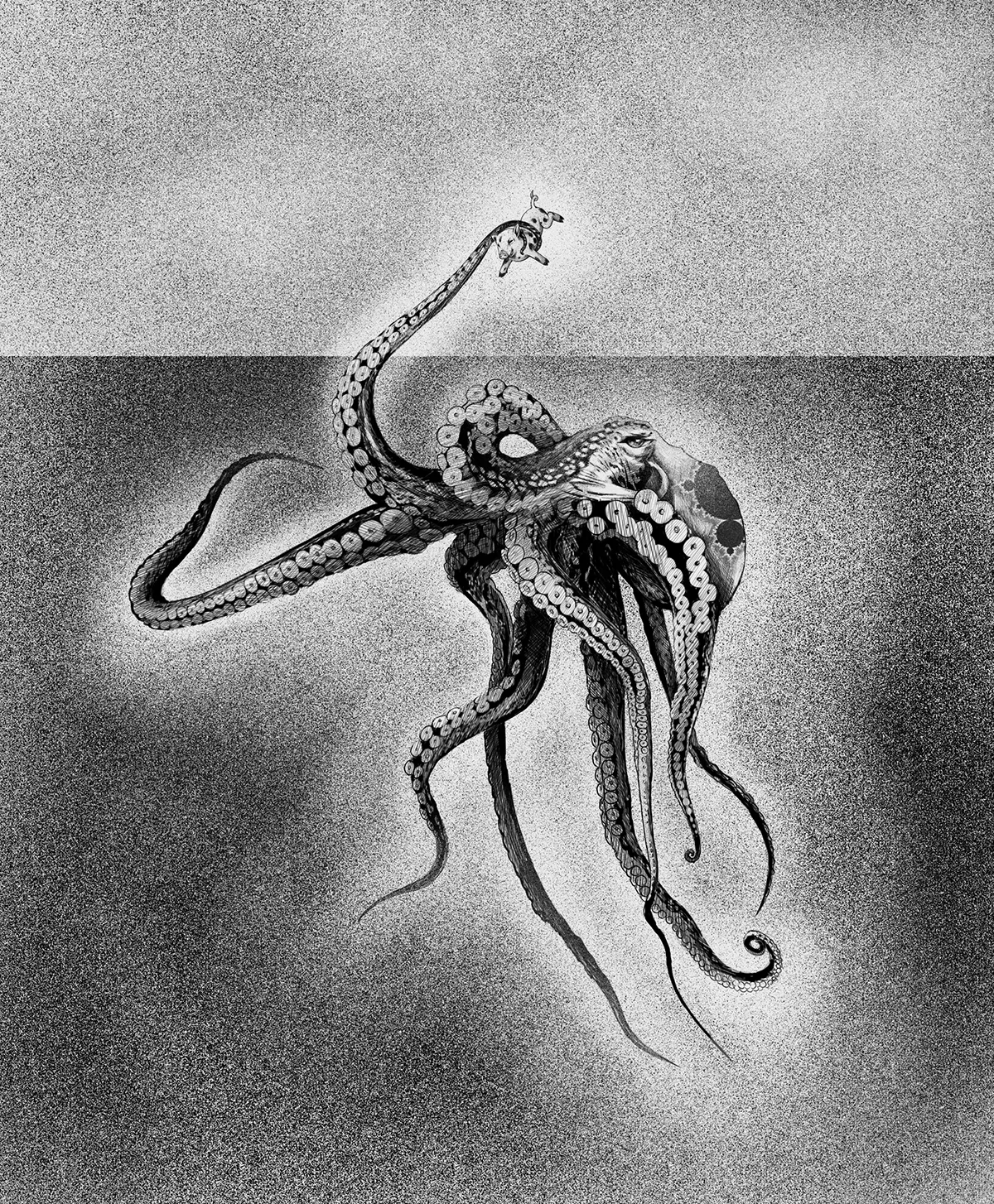

Reminders of his salad days were stitched all over his DNA. Xoz was twenty times heavier than the average Enteroctopus dofleini, and would’ve admitted he was mostly an octopus, “if it weren’t for the genomic bells and whistles inherent to trinomial nomenclature.”

Like all Enteroctopus dofleini retiarius, Xoz had an azide detonator attached to one of his three hearts. Unlike the rest, he was banned on every continent.

Tippi was up in the schisto, wet and annoyed.

“Xoz, you cnidarian! What was that for?”

A smear of a tentacle cinched at her sides. The pig was high in the air, between the green moss and red mollusk, sandwiched by unreality.

“Apologies! My fault!”

“I dub you ‘Mr. Radial Symmetry’!” she raged. “Now and forever, your mouth is your anus!”

“I am truly sorry!”

“Respect the slogan, the Urban Infiltration Unit’s in effect!”

“I know, I know!”

“And you know I hate going under!”

“I can explain!”

“Then explain why you’re red right now. Turn something else, it feels like I’m talking to an eye floater.”

“Do you want me in matte or neon?”

“Neon, obviously!”

The tentacle appeared around her, and Xoz blazed into existence.

His arm was an electric black, shimmering obsidian, like a galaxy burnished. Absence and maximalism, at the same primal scream: that was the pig’s roommate.

Biolumi patterns covered the tentacle. Violet Mandelbrot sets seeped out of his suckers, a parade of fractal applemen. Under his flesh, a jagged outline of his circulatory system boiled, a cupric blue.

Xoz gave his skin a twitch, and the retinue of applemen danced down his tentacle, pausing only to slip by a sloppy ringlet of pigment, like a cracked LCD; his dazzcamo pooled where his meat regenerated.

After fifty feet, the Mandelbrot sets melted into his crag-o’-mantle, which bore his organs and eyes; it was the least of his 463 kilos. Experience had taught Xoz to keep his crag placid, and triage effort to his extremities. Still, his eyes had a habit of rolling across the crag-o’-mantle, in opposite directions; they were tan like Jovian ammonia, and his pupils were black rectangles.

The mollusk found eye contact atavistic, so his mood migrated to his tentacles. In the trench, his seven arms burned, anthracite bright and frittering like solar flares. Most days, they bobbed.

Humanity never cracked artificial gravity at economy pricing. As a result, Xoz’s tentacles were brutal engines, built to thrash and bully the low-grav guts of non-lux vessels. Each of his hulking limbs bore a smashed-LCD ringlet, and one arm wore three.

In micrograv, Xoz relied on his ink sac for locomotion. It had been hollowed and drained for gas release, which was typical of retiarii. Underwater, he favored jet propulsion, like his foremothers. Swimming in the cistern, Xoz could hit 80 knots in .072 seconds. If Tippi took her eyes off him, he’d reappear across the trench in a blink, to her confusion and delight.

Xoz’s chromatophores were the best $10.919 trillion federal could buy. His skin was so expensive, its budget cannibalized the usual retiarii kit. His genetics held no space for deadweight like dermal recall, empathy matching, and kraken oats.

Had Tippi been a human, or a light-mod sapiens varietal, Xoz’s dazzcamo would’ve already infected her optic nerve with phototheistic psychoparasites. But she was a teacup hypermini, so all she saw were funny purple ovals.

Xoz boiled in the trench, a drowned sun. He was a lineage of one, and the death of the entire retiarius line.

“I have good and bad news,” he confessed. “In unequal ratios.”

“Enough fractions!” yammered Tippi. “Good news first!”

“Lina’s fine,” said Xoz. “And says we should play chess.”

“That’s unexpected. What’s the bad news?”

“Pig! I’m on drugs!”

Outro: Harris – “Im Club”